ASSESSMENTS

China Fears U.S. Missile System in South Korea

Mar 27, 2015 | 09:05 GMT

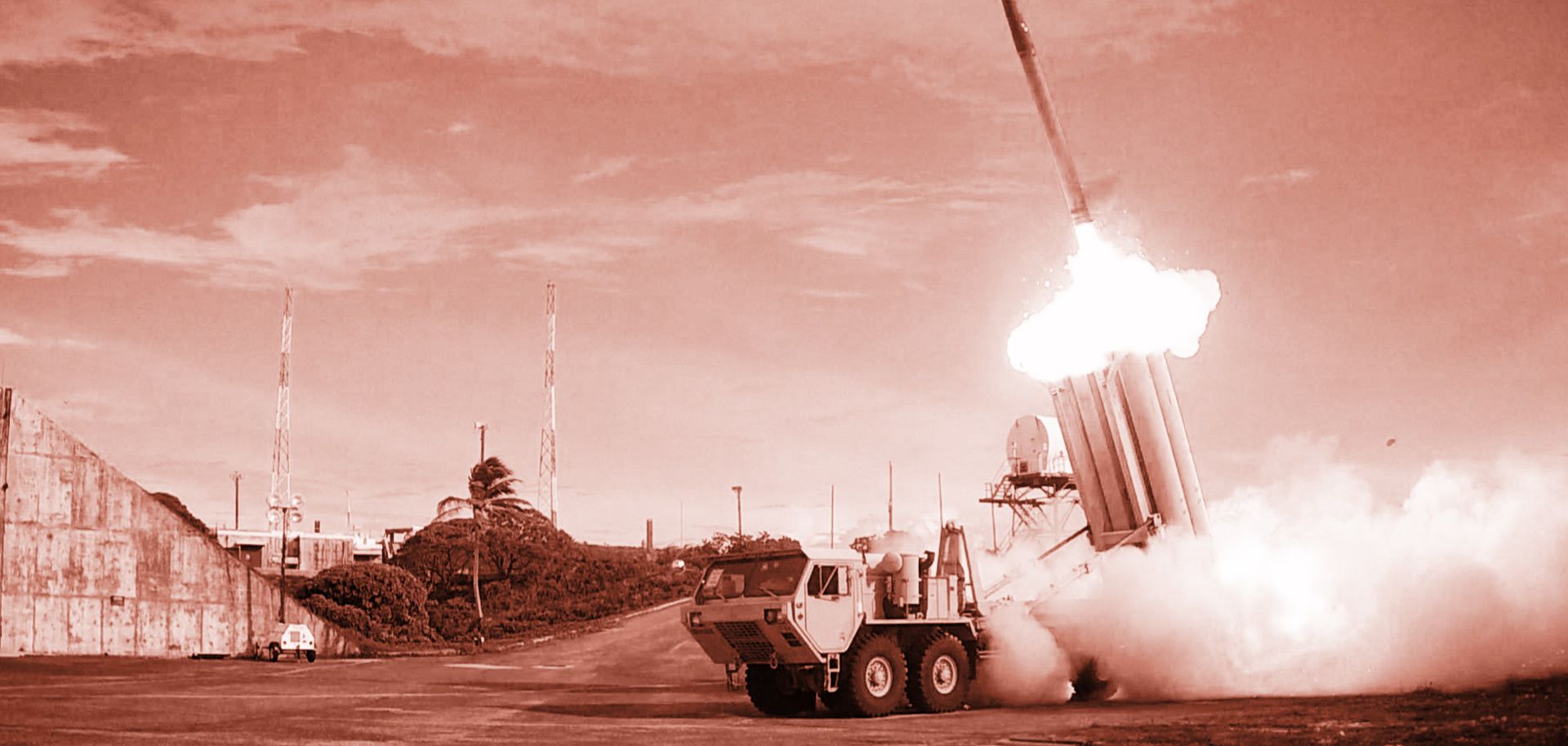

(Wikimedia Commons)

Summary

Editor's Note: This piece lays out competing U.S. and Chinese strategies that underscore a controversy over a new U.S. proposal to deploy an anti-ballistic missile system in South Korea. An earlier analysis explored the tensions between Washington and Seoul over this system.

South Korea and the United States are beginning to discuss plans to deploy a U.S. Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense anti-ballistic missile system on the Korean Peninsula. The system, known as THAAD, would protect against tactical and theater ballistic missiles at ranges up to 200 kilometers (124 miles) and altitudes up to 150 kilometers. It would also be equipped with X-band radar that has a much longer range. South Korea's hesitation to accept the system has led to a public debate and, as a result, to China voicing strong opposition to the plan. Beijing openly reminded Seoul that China, not the United States, is South Korea's major trading partner and that a deployment could lead to significant political and economic costs. Seoul has reacted by saying that it will make a decision on THAAD based on its own national interests, not Chinese pressure.

China's strong stance against THAAD is quixotic — the system is an area defense system, meaning it would defend against missiles falling only on South Korea. Beijing, however, has larger concerns. It sees the deployment of the system as the potential start of greater U.S. deployment of anti-ballistic missile systems on the Asian mainland. Ultimately, China's rhetoric toward South Korea reflects Beijing's concern that enhanced U.S. anti-ballistic missile capabilities would weaken Chinese nuclear deterrence and thus shift the balance in the Pacific.

Subscribe Now

SubscribeAlready have an account?