South Korea's enormous, family-controlled conglomerates, or chaebols, form the backbone of the country's export-dependent economy. Their clout grew because the industries composing the conglomerates were poised to meet growing demand after World War II for capital-intensive heavy industrial goods (and later, electronics). More directly, their influence is the product of a concerted push by the government in Seoul to transform the country from a poor, war-torn agricultural society into a manufacturing giant, an ambition it achieved in the span of a few decades. As key instruments of the transformation, chaebols benefited from unparalleled access to and support from the state.

Still, given their overwhelming importance, chaebols have long been targets of criticism and calls for reform. Detractors demand that chaebols increase transparency and improve their corporate governance, making them less prone to corruption and putting a check on their monopolistic tendencies. The South Korean government's struggle to regulate the chaebols dates to the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act of 1980, which created the country's leading antitrust watchdog, the Korea Fair Trade Commission. The law came, in part, as a response to growing fears that as chaebols gained control over businesses outside their initial core industries, they would squeeze out the country's small and medium-sized enterprises, the foundation of employment nationwide. But though the law created a framework for the chaebols' regulation, it did little to restrain their expansion. Despite persistent government efforts to tighten controls on the conglomerates, there was little Seoul could do to constrain them without slowing the economy.

The combination of insufficient oversight and minimal transparency set the stage for economic problems to arise. By the mid-1990s, easy access to financing had led to spiraling overinvestment by chaebols, sending their debt-to-equity ratios skyrocketing. Unsurprisingly, during the Asian financial crisis in 1997, the collapse of South Korea's currency, the won, gave way to a liquidity crunch as small and medium-sized enterprises crumbled and chaebols struggled to service their mounting debts. The crisis ushered in a second wave of chaebol reform and restructuring efforts. Those helped to lower chaebol debt levels and improve transparency and productivity within the conglomerates. But enduring economic volatility in the early 2000s and the need to maintain economic stability blunted interest in continuing reforms that might provoke backlash from leading chaebols.

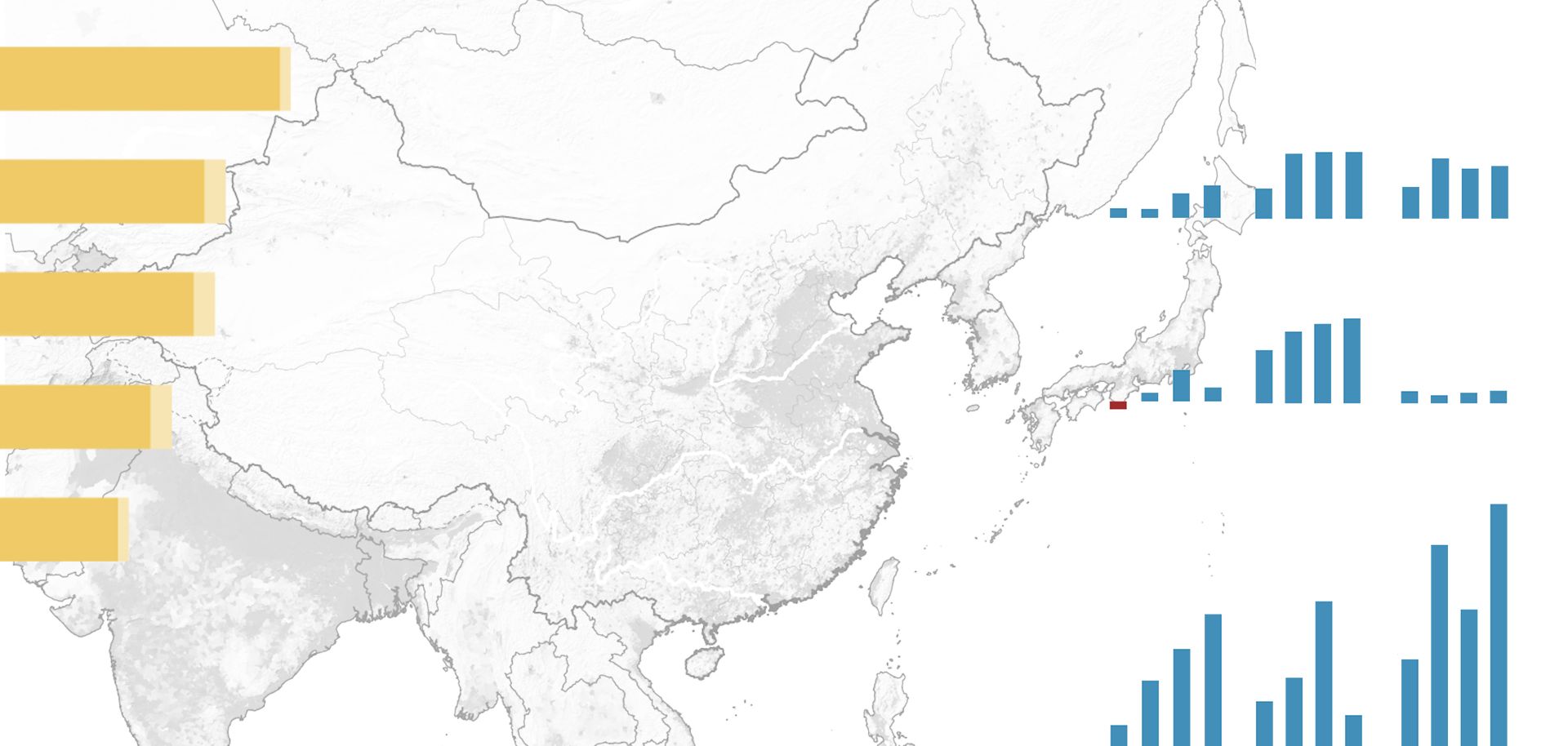

Buttressed by rising demand from China and a steady recovery in U.S. consumption, South Korean exports rose by 57 percent from 2009 to 2014. Popular opinion of chaebols, which had been negative for much of the previous 15 years, softened somewhat as they outperformed many of their global competitors. Meanwhile, the characteristics that had subjected chaebols to criticism in the past — family control and opaque corporate governance — were increasingly credited with enabling the conglomerates to think and act strategically. Although many South Korean governments have promised to rein in the chaebols, they are still as influential today as they have ever been.